After an orgy of Western press reports on the Pussy Riot affair (playing mainly to stereotypes and ignoring the genuine radicalism of the group), any reports about further repression in Russia in the Western press have since been few and far between. Perhaps because it started to get sick of its own voice or that the Pussy Riot affair was the story that sold and those lingering in jail after the May 6th repression is a story that won’t sell. It is hard to fathom how sickening and grotesque the Pussy Riot story has developed- while two members still languish in jail well-known multi millionaire singers find ways of profiting not just to boost their image but also materially from their predicament Madonna grabs the money while Pussy Riot languish. After the court sentence, it became clear that something had changed in the country and the steady persecution of a number of the demonstrators present at the May 6th march as well as the kidnapping of one oppositionist and television show trials of others as well as the petty and irritating actions of the Investigation Committee with regard to one of Russia’s most respected Marxist scholars, Boris Kagarlitsky, has led some to posit strange parallels with Stalin’s Great Terror. This, of course, seems rather too far-fetched as Kagarlitsky himself pointed out: it is in own way insulting to the memory of those who perished in the mid and late 1930s and at other particularly repressive periods of Stalin’s rule.

Yet more recent events at Kopeisk prison near Chelyabinsk seem to demonstrate that repression in Russia is still much more a serious and unpleasant fact than many would like to admit. This time around after Pussy Riot further international solidarity is thin in the ground apart from a few Marxist and radical thinkers and figures such as Ken Ken Loach who have shown some of the generous solidarity that others are failing to show this time round. If, it seemed, that there was some case for talking about a certain apology of Putin’s Russia on the Left at some point in the recent past (due to understandable but miscontured concerns about Western imperialism), it is now clear that this is no longer the case. The setting up of the unpleasantly and vicious right wing Conservative Friends of Russia (with some links to fascist figures the truth about CFoR) clearly gives one a clear idea of where any apologia is coming from now.

In many ways the case of Kopeisk is rather indicative of how things develop in Russia- it is quite clear that some terrible things have been happening there but then there are a number of discourses which cover this up- the state discourse (broadcast on television) denying everything and then the ‘realist’ discourses of many kinds – either justifying, minimizing or putting things into perspective. These discourses crowd out the facts that can be established and crowd out the public resonance of these immense human rights violations. Many people know the facts – this video of torture in a prison camp had over 100,000 views and yet somehow people re-dimension even these facts.

Yet Kopeisk gathered little interest among the foreign correspondents – Masha Gessen wrote a small blog in the New York Times stating that “All anyone can be sure of is that near the city of Chelyabinsk, by the southern Urals, something horrible is going on.” Masha Gessen on Kopeisk but for others this is not news at all. The Guardian Russia correspondent went the furthest tweeting after news of beatings of relatives was reported that the “big news of the day was the break up of Russian pop group Via Gra” (although, to be fair, she has since published one article on prison brutality). Otherwise it was left to today’s Moscow Times to print an article which was, at the very least, more authoritative Jonathan Earle on Kopeisk The growing repression after May 6th seems to be a no-go area for many correspondents. The slow drip of trials, of small protest actions and the inevitable arrests of activists, the individuals picked off one by one at other times- accused of various spurious crimes, the interrogations and persecutions by detectives from Centre E – the new political police- all this continues day after day without much of a squeak from the international media (but then this follows a certain pattern – the horrendous police repression in parts of Southern Europe to the November 14th general strike also got little coverage).

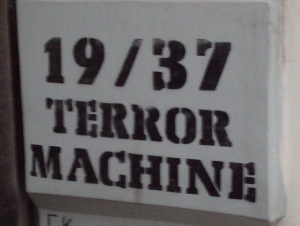

In Moscow there is no repeat of 1937 but the show trials are now organized on television with Arkady Mamontov a consummate substitute for Andrei Vishinsky. The accusations are as yet a little different – Mamontov’s febrile imagination is more inane and ridiculous (yet there are some takers for the idea that dances in cathedrals were organized from abroad). Nonetheless, the internet while generating irony, mobilizing scepticism and cynicism as well as parody, it only rarely mobilizes a certain amount of indignation and still not enough active resistance. Denouncing repression and saying that 1937 is at our doors may indeed be a favourite pastime for liberals, but the numbers of those who are really willing to turn up to unauthorized protests (and even many authorized protests) are still very small.

Regarding the large demonstrations of last winter, perhaps in retrospect, the writer Maksim Kantor got it most correct. Many went to the demonstrations for just about the same reason that people bought indulgences in the Middle Ages- a kind of absolution for being part and parcel of the Putin system for many years- having bartered their previous silence and consent, they now believed that, in some way, they could purchase some kind of moral distance from the system that only few had ever fought. After 6th May when the demonstration turned violent – through police disorganization- many of those who participated have now returned to their previous silence. Only the few, the minority, continue. The solitary pickets make their presence felt at the shameful court cases in which the repressed of May 6th are tried. The conformist liberals and systemic oppositionists will continue to find ways of making further indulgences while the small leftist and more active radical, liberal groups are among the only ones to actually organize (bearing as they do the brunt of the current repression), foreign correspondents will most probably continue to ignore this story (in favour of pop group break ups and the bureaucratic evils of dry cleaning), independent trade unionists in the provinces will continue to be beaten or jailed on spurious charges and new extractive capitalist gulags like Kopeisk will continue to spring up and operate until the system eventually collapses (perhaps due to some absurd scandal). Then, in the worst case scenario, the system won’t be rebuilt from below but from above by the Prokhorov’s of this world.

In any case at present the prisoners of this repression are slowly being forgotten- whether it be the Pussy Riot three victims both of millionnaire pop stars who have extracted profits from their name while feigning support and of their current jailor- the Russian state- or those like Vladimir Akimenkov (an activist arrested at the May 6th demonstration for very little indeed and who is now slowly going blind in a Russian prison- the judge sadistically stating that until he confesses he won’t get any medical attention). It may not be 1937 but the obscene repression visited on the (so far) few is sickening indeed. The very least they deserve is true international solidarity. Fortunately over the next few days this campaign will start with demonstrations at various Russian embassies in Europe. Yet there is more to be done and what needs to be done is to understand that repression in any country (whether it be the police repression in Genoa in 2001, or the repressive measures taken after the riots in the UK, or the present repression of participants of the May 6th demonstration in Bolotnaya Square should be met internationally. Each state has its own peculiarities (Russia’s riot police probably acted slightly less violently than the Italian riot police in Genoa but the vindictiveness and absolute corruption of its courts and prison system leaves no doubt that Russia has one of the most repressive regimes today which according to present trends is getting steadily more repressive). It is time that those fighting for international social justice realized that the Russian state is a threat to its own population precisely because it is building a ruthless and vicious capitalism that the George Osbourne’s and David Cameron’s of this world dream of.