It’s that time of year for book and film lists. I’ve been a slow reader this year and so maybe I’ll play around with a number of lists regarding the books that I have read, the books that I’ve started to read but will finish in 2018, the books that I’ve bought in 2017 and promise to myself that I’ll get round to reading them in 2018 (although fear that I may not get round to reading them before 2020), the books that I’m really ashamed about not having read, the books that haven’t been translated and prove that English-language publishing houses have followed the fashion noted by Juan Rodolfo Wilcock of employing farm animals as their readers or are run by the same kind of cultural isolationists that tend to predominate in the London film critic mafia.

Anyway here’s my list of books that I’ve read and have really enjoyed during 2017 (some of them published well before 2017) and other books awaiting my free time and so on.

Alexandra Petrova’s 2016 masterpiece Appendix which I’ve been reading and re-reading since its publication

The one major novel that was published back in 2016 and which I’ve been reading and rereading is a book which has yet to be translated but which I do hope to publish an English-language review of somewhere. This book is Alexandra Petrova’s 832 page novel Appendix. My review of it came out in Russian for the New Literary Observer (НЛО) in the late Spring and I’m hoping to rewrite my English-language review about the book soon. It won the Andrey Bely literature award last year but suffice it to say that not only I but many others, including one of Russia’s best literary critics, Alexander Skidan, believe it to a major literary breakthrough in Russian letters. Through eight major characters and numerous minor characters the novel takes up one of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s uncompleted projects of ‘translating’, or rather in Petrova’s case, ‘transplanting’ the Aeneid into contemporary Rome (and St Petersburg). Zinovy Zinik rightly chose it as one of his Books of the Year last year for the TLS and had this to say about it:

In her monumental novel Appendix (NLO, Moscow), Alexandra Petrova, an émigré Russian poet and translator, who moved to Italy in 1998, has managed to exorcize the traumas of her Soviet past by mingling them lyrically with those of idiosyncratic characters on the outskirts of life in a contemporary Rome unknown to foreign visitors.

It is rather impossible to summarise this novel in a few words but suffice it to say that its Rome is as memorable as the Romes of Pier Paolo Pasolini and Carlo Emilio Gadda and to me at least has something of those memorable foundational city novels of Latin American literature such as Marechal’s Adan Buenosayres. It is like those novels a most memorable depiction of migration and deftly avoids the autarkic moment of much contemporary Russian, European and British letters. It is too good a novel to be ignored by English-language publishers (and Italian-language ones at that) and let’s hope that some publisher has picked up on this genuine masterpiece.

I’m rather happy than a number of my recommedations for translations of foreign-language titles have been published in English. The book Sex of the Oppressed is now published by Publication Studio in a translation by Jonathan Platt and one of the titles I highlighted in another blog post, Nanni Balestrini’s Vogliamo Tutto, has been published by Verso after having come out in a small Australian book publishers, Telephone Publishing back in 2015. I am also delighted that Elsa Morante’s fascinating poetic tract The World Saved by Kids and Other Epics has found its way to an English-language publisher. 2018 should be the occasion for the long overdue publication of Larry Riley’s translation of Roberto Arlt’s The Flamethrowers, a book which was Number One in my list of books that needed to be published in my ‘If there were only another Feltrinelli’ blogpost back in 2013 way before I had even heard of Larry’s translation. Rachel Kushner’s novel of the same name is another novel I’ve finally got round to reading this year- it deserves considerable praise for its telling portrait of the Italian 1970s (Kushner was the author asked to write an introduction to Matt Holden’s Balestrini translation). Let’s hope that if Balestrini ever gets translated into Russian, Alexandra Petrova will get to write the introduction given her own treatment of the Italian 70s in her novel.

Matt Holden’s translation of Nanni Balestrini’s classic collective epic on the Italian ‘Hot Autumn (now republished by Verso)

Otherwise I’ve been mainly reading non-fiction this year. The two film books that mainly caught my attention were Jack Sargeant’s Flesh and Excess: On Underground Film. Those interested in what I have to say about the book can go to my review of it for Senses of Cinema but here is my concluding sentence regarding the importance of this book for any understanding of the other history of cinema:

When a major reimagining of film, and a rewriting of the “other history” of cinema is undertaken, Flesh and Excess will surely be seen as an urtext of this grand alternative history.

An image from a film by Aryan Kaganof which serves as the cover for Jack Sargeant’s excellent new work on Underground Cinema Flesh and Excess.

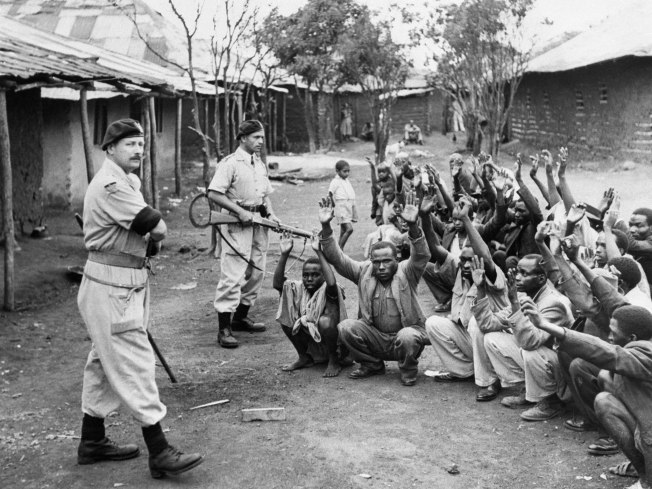

I’m presently reading Duncan Ritchie’s excellent overall history of Underground Cinema which takes a more straightforwardly historical approach. So far I think it is excellent and is a great accompaniment to Sargeant’s book. I’ll never tire of recommending, too, Mikhail Trofimenkov’s Film Theatre of War, which I still think is the film title that people in the English-language film publishing world should translate. Any radical political publisher would also be wise to get their hands on such a title given its superb rediscovery of the history of anti-colonial cinema. (I’ve been banging on about this title for some time now and hope people start waking up to its significance).

Another film book that came out this year and which I’ve managed to read is Werner Schroeter’s own account of his life. A memoir written with the help of the critic and his friend , Claudia Lenssen, Days of Twilight Nights of Frenzy deserves notice. I’ve seen little of Schroeter on the big screen but his Reign of Naples will always be in my list of top films. Schroeter may not be as much a household name as Fassbinder but it would be a terrible shame if he were written of film history. He merits a major retrospective just as this title deserves a large readership.

Two more film-related books that I’ve read are Philip Cavendish’s The Men With the Movie Camera: The Poetics of Visual Style in Soviet Avant-Garde Cinema of the 1920s and Agon Hamza‘s more philosophy-related Althusser and Pasolini: Philosophy, Marxism and Film. The former is a welcome look at the stories of the unsung cinematographers behind the 1920s breakthroughs in Soviet cinema and the latter is a fascinating attempt to talk of two rarely combined authors Louis Althusser and Pier Paolo Pasolini through the prism of philosophy and film. In Russian I’ve read the recently published biography of Gennady Shpalikov, the Soviet Vigo. Director of just one film but author of a number of classics, Shpalikov would have celebrated his 80th birthday this year were it not for his tragic suicide at the age of 37. Nontheless, the traces he left in cinema deserve to be picked up. Anataoly Kulyagin’s biography fills in some of the details of Shpalikov’s life but it is Shpalikov’s poems, scripts and stories that truly deserve to be published outside of Russia along with a retrospective of the films that he scripted (together with his own A Long Happy Life).

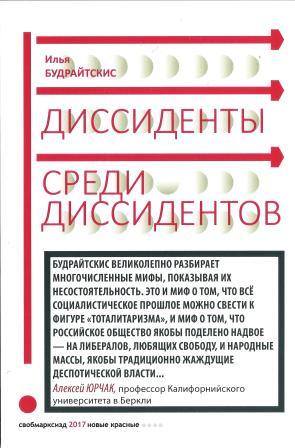

Of the other Russian books read this year, I have already reviewed Ilya Budraitskis’ Dissidents Among Dissidents for this blog, another book that merits a long review is one of the major titles to come out on the Left Russian Avant-Garde of the 1920s. Published several years ago for the Higher School of Economics publishing house, Igor Chubarov’s The Collective Sensibility: theories and practices of the Left Avant-Garde is a major study of all the various avant-gardes that made early Soviet art of such universal importance. Chubarov is a leading contemporary theorist in Russia and it is about time that the western Left discovered more of the kind of debate that is going on in Russia itself. Both Budraitskis and Chubarov’s work in translationwould certainly help informed western Leftists to orientate themselves to further understanding the real legacy of the October Revolution in both arts and politics. Talking about the legacy of the Russian Revolution, or rather the complexities of the Soviet Century, Mikhail Ryklin’s own look at this through the optic of his own family history, Doomed Icarus which has recently been published by НЛО (New Literary Observer) books, is well worth reading (or well worth insisting that an English-language translation of it be published).

Mikhail Ryklin’s look at sections of the Soviet Century through his own family history, Doomed Icarus. An author long worth translating into English.

Having contributed with a translation and commentary on one of the most fascinating texts of the great Soviet philosopher Evald Ilyenkov (Cosmology of the Spirit), for the most recent issue of Stasis Journal, it is vital to mention the recent publications of books of Ilyenkov’s early essays. Two volumes have been published by Moscow’s Kanon publisher of texts and material relating to Ilyenkov’s philosophical thought. While an earlier volume was devoted to the circumstances surrounding the famous theses that Ilyenkov and Korovikov published and tried to discuss in the early post-Stalinist Philosophy Faculty of Moscow State University, this new volume includes the very texts of these theses, hitherto not yet unpublished but undiscovered in full as well as many other pieces by Ilyenkov both previously published and hotherto unpublished. These texts come alongside major text by Vladislav Lektorsky, the late Ilya Raskin and Ilyenkov’s daughter Elena Illesh. Ilyenkov has yet to be given the recognition he merits but it does seem that his star is on the rise. Especially with a new documentary film made about his life by filmmakers Pyotr Laden and Sasha Rozhkov. Other Soviet philosophy books read or initiated have included Sergei Mareev’s new book on Vygotsky, and the book that most requires reading in 2018 are the unpublished Vygotsky writings from his notebooks and edited by the superb Vygostky scholar Ekaterina Zavershneva. A real treat.

Selections from the notebook of Lev Vygotsky, published in Russia this year.

My reading of the Soviet historian Boris Porshnev has commenced this year with possibly his most accessible book, an account of the life of Jean Meslier (the first promoter of atheism, himself a priest, and the presumed author of the famous quote regarding entrails of priest and noblemen: “He wished that all the world’s high and noble would be hanged and strangled with the entrails of the priests.“. Porshnev biography is an excellent tract trying to rescue Meslier from the false redaction of his thoughts by Voltaire. Porshnev convincingly argues that Meslier not only the first atheist,was also very much a communist thinker. I’m not sure whether Porshnev’s biography has been reprinted much since it was first published in the mid 1960s but let’s hope that it will get some notice once again and not just in Russia.

Boris Porshnev’s excellent biography of atheist priest Jean Meslier and presumed author of celebrated quote about strangling noblemen with entrails of priests.

Porshnev has an essay devoted to him in the recent edition of Stasis which I mentioned above, and I’m glad to say that a copy of his book On the Origin of Human History is on my desk read to be rea in early 2018.

Other authors read in 2017 have included John Berger, notably his Landscapes book, Bento’s Sketchbook and a number of his Portraits. I’d loved Zinovy Zinik’s short History Thieves as much for its form as its storytelling– I’ve always wanted to compose a work that is ninety per cent footnotes to ten per cent text so Zinik’s nod in that direction delighted me more than irritated. I hope that 2018 will be the year when I catch up on his other works.

What more to add? It has also been a year of reading some Enzo Traverso and Marc Auge. I’ve finally got round to reading Andrei Bitov’s A Captive of the Caucasus. I’ve started on Catriona Kelly’s promising St Petersburg: Shadows of the Past. And while it’s been the centenary of the Russian Revolution the only major work I’ve read on that subject has been China Mieville’s October. Wonderful narration that sometimes veers into depicting the Revolution as Slapstick (the story of Lenin’s wig for some reason often comes to mind). I don’t know if I’ll get round to reading Danilkin’s biography of Lenin in 2018, but I really do hope to read the various essays by Yaroslav Leontiev in the recently published book Reds. Jointly written with Yevgeny Matonin it is sure to tell us about other leftist figures and forces in the Russian Revolution that we rarely hear about, less crassly than James Medhurst does.

I started Langston Hughes’ excellent autobiography and hope to finish it in January. Who knows which of these books (old and new) I’ve got colonising my workdesk I’ll get to read but, yes, there’s hope for them all in 2018:

- Giorgio Agamben – Che cos’e la filosofia? (What is Philosophy?)

- Alexander Skidan – Сумма Поэтики (Summa poetica)

- Oxana Timofeeva – История Животных (The History of Animals)

- Victor Misiano – “Другой” и Разные (The ‘other’ and various)

- Alexander Brener – Ка, или Тайные, но Истинные истории искусства (Ka, or the secret but truthful histories of art)

- Louis Althusser – The Future Lasts Forever

- A. Meshcheryakov – Awakening to Life

- Elena Aleksieva – The Nobel Laureate

- Ricardo Piglia – La Forma Inicial (Conversaciones en Princton) – (Conversations in Princeton)

- Georg Lukacs – The Theory of the Novel

- The Practical Essence of Man: The ‘Activity Approach’ in Late Soviet Philosophy (ed by Vesa Oittinen and Andrei Maidansky)

- Edward Upwards – In the Thirties

etc, etc, etc.

And then there’s the books still yet to be purchased:

- Georg Lukacs – The Destruction of Reason

- Sarah Schulman- The gentrification of the Mind: Witness to a Lost Generation

- the novels of Aleksandr Ilyanen

- Eugenie Zvonkine’s study of Kira Muratova

- Franco Fortini’s Attraverso Pasolini

- the Katerina Clark books I’ve yet to read (especially her ‘Moscow, the fourth Rome)

- the Maxim Kantor novels still unread

- Ricardo Piglia’s Diaries of Emilio Renzi

- some of China Mieville’s sci-fi stuff

- Marco Bertozzi’s history of Italian Documentary film

- Benjamin Noys – The Persistence of the Negative: A Critique of Contemporary Continental Theory

- Alexei Tsvetkov – (Король Утопленников) King of the Drowned

etc, etc, etc

And then there’s that copy of The Mad Patagonian by Javier Pedro Zabala that the American author Rick Harsch has lying in wait for me as soon as I set foot in Trieste again and which will undoubtedly set back my other reading by a month or so given its purpotedly monstrous size. Of course there is Harsch’s The Skulls of Istria to read too…

A copy of Alexei Tsvetkov’s latest book published by the radical Russian publisher ‘Free Marxist Press’.

A copy of Alexei Tsvetkov’s latest book published by the radical Russian publisher ‘Free Marxist Press’. The writer Aleksei Tsvetkov at Tsiolkovsky bookshop.

The writer Aleksei Tsvetkov at Tsiolkovsky bookshop.