One of those who attended the talk to promote the book of writings and memories about Stas Markelov and Nastya Baburova which I wrote about in my previous post was Vladimir Akimenkov, released in the recent amnesty after he was unjustly imprisoned in the Bolotnaya case. He has also been back to the Bolotnaya courtroom to support former fellow defendants. Here for the excellent new site in Russian Open Left or Окритая Левая, he talks about his detention and imprisonment, his life before that as a political activist and his life after his release under the recent amnesty.

Taken from the Open Left site: http://openleft.ru/?p=1030

Vladimir Akimenkov “The Bolotnaya Case is an attempt to destroy the Left opposition”

Aleksandra Markova

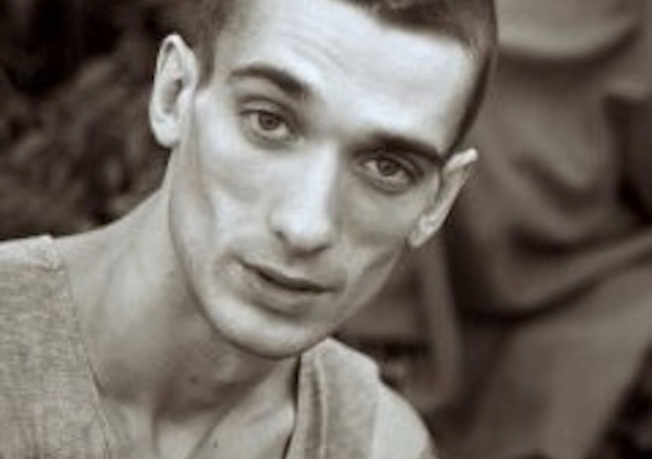

Vladimir Akimenkov arrested at the Bolotnaya demonstration

Half of the people arrested in the Bolotnaya Case are Left activists. “Open Left” spoke with one of them after he was freed in the recent amnesty.

Aleksandra Morozova: I went with Vladimir Akimenkov to a self-service restaurant. He found it difficult to distinguish the food on display and I helped him out with his order. Vladimir’s bad eyesight after eighteen months of detention has only got worse. It is a week after his release from jail and he still finds it difficult to get used to the city bustle feeling joyful but rather bewildered. Vladimir is an activist of the Left Front and was one of the accused in the Bolotnaya Case included in the amnesty.

Aleksandra Markova: How did you get involved with the Left movement?

Vladimir Akimenkov: I’ve long been interested in politics, I read a lot on the subject since my adolescent years. I became an activist in 2007 on the wave of the “March of the Dissenters” at that time. I evolved from being a Liberal to socialist views in that time, and for the past four years I have been a member of the “Left Front”

Have you been arrested in the past four years?

Yes, more than once I’ve been detained both on ‘legal’ and ‘illegal’ actions, as have a large number of my comrades. In 2010 I was tried for the article 282 on extremist activity for leaflets with the slogan “Eliminate the slave in yourself”. The text was a very moderate one. I then received a one-year suspended sentence. Though I’ve seen many cases in which people have been jailed and maimed for political actions and I knew that this could also happen to me.

Tell us about the incident which led to your arrest on the ‘March of Millions’.

I found myself in the crush that was provoked by the police. The police arbitraily restricted the territory where the event was going to take place, they blocked the square, cramped the entrance and as a result we got stuck inside a police cordon. The columns of demonstrators could not get to the square. In spite of the fact that the pressure from the crowd behind grew, the police moved two steps forward two steps and people, in order not to be crushed , escaped from the cordon. As a result a fight started and the police began to beat demonstrators. I shouted out “What are you doing, stop beating people” and as a result of this they grabbed me and dragged me to a police van. According to the accusation, I threw a flagpole at the police cordon. This is a lie. In the case materials there is not (and could not possibly be) a video which supports the position of the prosecution case. It is based simply on false claims of the Moscow OMON (the riot police). Let’s not forget that members of the riot police were given free flats for the way they handled the crackdown on the March of the Millions. It is clear that we are political prisoners, we were arrested for the fact that we expressed our position. Almost two thousand people could not come because they were forceably taken off the trains.

The March of the Millions, unlike the previous actions, was comprised of significantly large numbers of leftists. How do you think that the Bolotnaya Case is linked to this fact? Is there a possibility that the authorities were afraid that the protest was moving radically to the left?

Yes, I think that the authorities were fearful of the protest moving leftwards. On the March of Millions there were large columns of the Left Front, the Russian Socialist Movement, anarchists and a strong column from the universities and educational spheres [protesting against the growing privatization of education – trans. note]. On the whole social slogans were dominant. I believe that the Bolotnaya Case was to a significant extent directed towards defeating the left opposition. But the crackdown was unsuccessful, we have overcome this stage and come out of it stronger, the struggle continues. At the same time I would like to remark that amongst the people involved in the Bolotnaya case there were people who were for the first time at a demonstration. Ending up in jail has made them more conscious and politicised them.

Akimenkov brought to trial

Tell us about the conditions in the prison.

In my case the number of detainees corresponded to the number of prison bunks, but in any case it was rather overcrowded. The Sanitary regulations and standards of four square metres for each detainee were not observed. In the last cell where I stayed, there were three people in an area of 9 square metres. In some places the surface of the walls are very rough and when you lie close to them it is easy to get badly scratched when you sleep. Prison food is very badly prepared, it was not only tasteless but also at times even harmful to one’s health. In terms of our subsistence we were assisted by parcels given by friends and relatives.

Was there a period when you found yourself in the prison hospital? What were the conditions like there, were you given the treatment you needed?

The hospital were themselves very much prison-like quarters. I was there for more than a month and a half, although I only expected to be there for three weeks. They twice called me there for observation but the results, to my mind, were falsified. According to the medical note, the condition of my health was satisfactory and I can see well. But in reality I can see practically nothing from my left eye. Also I have quite a few more problems with my health. In general both in the prison and in the hospital I only felt contempt from the administration regarding the health of prisoners. They did not treat us as human beings and even the implementation of legal requirements were only achieved after a large number of written claims. I want to thank the Public Monitoring Committee for the fact that they kept our case under their supervision and that we could get at least some of our rights observed.

How did your fellow inmates relate to political prisoners?

I felt a sense of respect from the part of completely different types of prisoners. Among fellow inmates there were those who consciously chose a criminal path in life, there were people from business, there were drug users or people detained for the possession of drugs. There were many migrants from various countries, even from European countries. In spite of the fact that we stood out from the general mass of prisoners, we managed to find a common language with nearly all the other prisoners. People recognised that we were in jail for the rights of the people, and so they respected us. Even in the prison vans when we were transferred people asked to be sent to those blocks where we were going to.

How has your life changed since you left jail? How have friends, colleagues and relatives reacted to your release?

I was only working episodically and I communicate with my relatives only rarely. Basically my circle of friends mainly include other social activists and I have had a great deal of from support from these circles. I have had a very eventful week since I’ve been released. It is nice to find oneself in a more relaxed and freer environment, to communicate with people who you underrstand and who understand you. Today, for example, I managed to attend two trials- those of the case against Udaltsov and Razvozhaev and the setencing of Danil Konstantinov. It was important for me to see these people who I’ve been acquainated with, and that they saw me and that they would get some cheer from that. I have also noted that strangers have begun to recognise me in the street and have shook my hand. But I can’t say that this always pleases me.

Do you have any plans for the days of action (against political repression and xenophobia) from January 18- January 26th?

So far I have no concrete plans, but I will take an active part in these and call on others to participate. We need to organise a number of powerful protest actions- meetings, concerts. The actions should take place not only in Moscow but also in the Russian regions and abroad. The more people that show that they support the freeing of Bolotnaya prisoners , the earlier that the release of those remaining in detention will become a possibility. We must not allow people to receive terms of 7 or 8 years for nothing, or simply for actions of self defence or defending people nearby. However pompous this may sound it is now that we are forming our future and the future of our children. If the state condemns the Bolotnaya prisoners then in the future the crackdown will be even worse.

Aleksandra Morozova – activist and journalist.

The arrest of another Bolotnaya prisoner, Alexandra Dukhanina who remains in jail.